What is Safety Culture?

The concept of safety culture has gained more attention in high-hazard industries as more safety practitioners see the influence that workers’ attitudes and behaviors have on the causes and effects of workplace incidents.

![]()

These attitudes and behaviors are shaped largely by the company’s workplace safety culture and its existing safety procedures.

The 4 Major Characteristics of Safety Cultures are Positive, Negative, Proactive, and Reactive

Negative Safety Culture: Negative and reactive safety cultures are unable to prevent workplace safety incidents.

In a negative safety culture, it is not uncommon for workers to feel pressured to bend or break safety rules or safe work procedures to meet deadlines or production goals. 2,3

Reactive Safety Culture: A negative safety culture paired with a reactive safety culture ensures that sooner or later the system will fail the workers it is supposed to protect, and safety professionals have begun to see this.

Positive Safety Culture: A major indicator of a positive safety culture is the quality and effectiveness of its communication.

Good communication in the workplace plays a critical role in shaping the safety culture and achieving safety goals and preventing incidents. When communication throughout all levels of an organization is strong, open, and meaningful, a positive safety culture follows.

Proactive Safety Culture: Positive safety cultures and proactive safety cultures work hand-in-hand, just as negative safety cultures are both cause and consequence of reactive safety cultures.

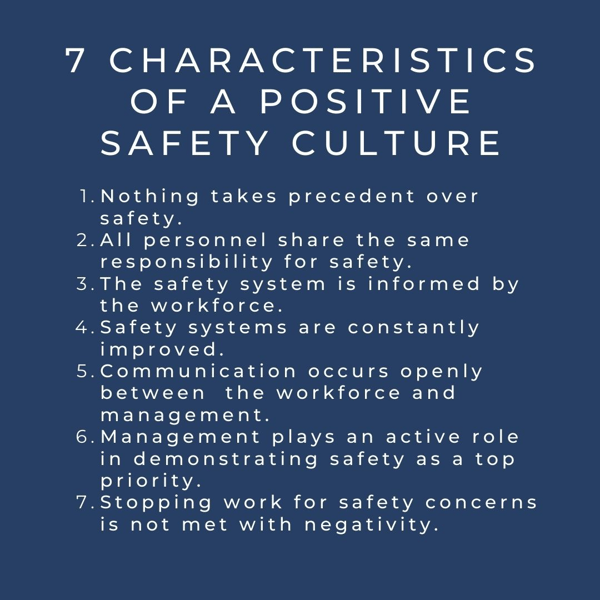

So, if you are a safety professional tasked with updating and improving your company safety culture, you can start by focusing on these 7 main characteristics of a positive safety culture:

In A Positive Safety Culture, Nothing Takes Precedence Over Safe Work Under Any Circumstances

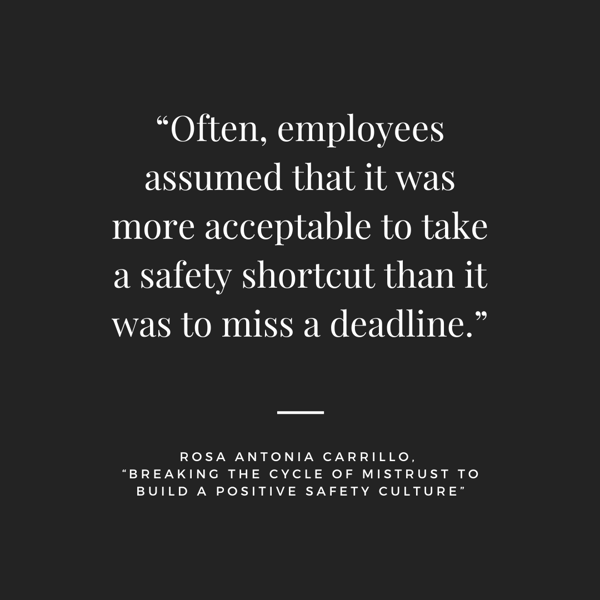

The workforce never feels as if safe work procedures are an obstacle to getting their tasks done correctly, on time, and without reprimand. The keyword here is “feels."

How do you get your workforce to feel the same safety priorities that you do?

Through effective communication, says Rosa Antonia Carrillo in her article for EHS Today.

So, if your employees are continuing to take safety risks despite your focus on making safety a priority, you may need to evaluate how effective the communication is between your company’s management and its workforce.

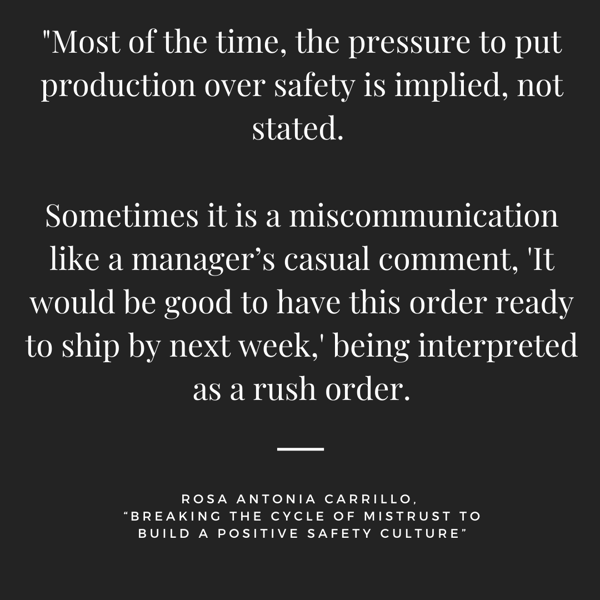

Because sometimes, the most innocent comment of urgency may influence workers to speed up, take short-cuts, and neglect existing safety practices.

If employees are under the impression, for any reason, that safety rules must be broken to achieve the results that management wants, any existing safety system, no matter how great, cannot protect them.

In a Positive Safety Culture, All Personnel, From the Front Line to Senior Leadership Share the Same Responsibility for Safe Work

If you want to keep your workforce safe, accountability is key.

Complacency and ineffective safety-related communication can lead to lapses in accountability if your company has a negative safety culture.

A positive safety culture shows compassion to spark positive change and does not blame or reprimand others.

At a high-hazard operation with a negative safety culture, workers often feel that supervisors and company managers have little concern for their well-being.

Carrillo’s article links this symptom of a negative culture back to communication issues: “Of course, managers did care, but often they did not understand the importance of expressing that care.”

The managers that employees valued and trusted were those who “talked to people one-on-one, gathered their opinions, their concerns and ideas, and acted on them.” 2 So, not only do managers have to be good communicators, they also have to take accountability and act on issues.

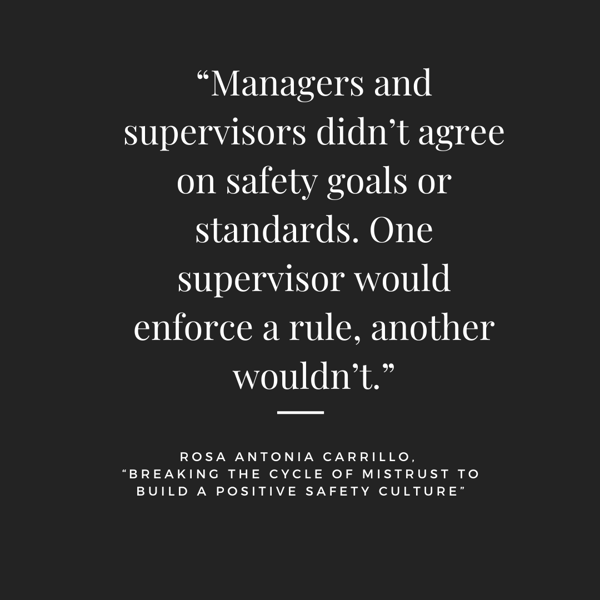

Seems simple. However, that double-standards are all too prevalent in negative safety cultures.

“People were not disciplined for failing to use proper personal protective equipment (PPE), but they were punished for accidents. Managers were seen walking through the plant without proper protection. Management wanted employees to remind each other to wear their PPE, but employees felt that constituted ‘enforcing the rules’, which is a management responsibility.

Thus, employees felt management was sidestepping its responsibilities.”2

In a positive safety culture, all personnel (regardless of position, job description, or time spent at the worksite) have an equal responsibility in keeping themselves and each other safe, and holding themselves and each other accountable.

Management should lead by example and not just talk the talk but also walk the walk.

In a Positive Safety Culture, the Safety System is Informed by the Workforce, Not Designed and Enforced Only by Management

Even if you think you have a great, positive safety culture, your workers’ input is critical to ensure it actually works to reduce incidents.

Why?

Because it needs to be in their language and suited to their needs and the pressures of their jobs.

Workers will disregard official safe work procedures if they are difficult to understand, use technical vocabulary or jargon, or are in an entirely different language than what your workforce speaks!

Your procedures also need to reflect the experience of your workers on the job.

Here’s an example of what happens when a safety system is implemented from the top-down, without any worker input:

The crew felt they had little in common with the managers who had devised the new safety culture with which they were being asked to comply. Process cleaner Luca expressed the alienation he felt about pressure from…management to subscribe to a total safety culture created through slogans such as Wait 1.

Wait 1 was supposed to prompt a worker to pause before embarking on a task that might be hazardous. Luca believed that top managers did not have to worry themselves about safety in their own work.

“They don’t have to Wait 1 before they put their hands on the keyboard, or look before they walk down the corridor” . . . In Luca’s mind the requirements for managerial safety were very different from what was required to achieve operational safety . . .

Operating manuals, which were supposed to direct the crew’s every task, were inadequate, so the workers had developed their own alternatives.

The crews believed strongly that their own understanding of safety was superior to that prompted by managers in offices.3

In a positive safety culture, safety systems and procedures represent the experiences and tasks of the workers realistically through their own input. Not including their input devalues their first-hand experience and expertise, and maintains a cultural rift between them and their managers. This cultural rift further contributes to poor communication and miscommunications that lead to safety incidents.

In a Positive Safety Culture, Existing Safety Systems are Constantly Improved

So, you’ve had a period of incident-free work and you think your safety systems are up-to-par.

Maybe so.

But are you going to wait for the next accident to put your practices back into question?

Or can you make changes every day to ensure that your system continues to be up-to-par and prevent incidents before they happen (#proactivesafety)?

The answer is yes, of course. You can make changes to prevent accidents every day.

How?

Three tools:

- Communication (yes, we already talked about it above)

- Trust and accountability (talked about that, too)

- Proactive practices (didn’t talk about that yet):

A Positive Safety Culture Understands that Incident-free Work is the Result of Continuous Attention to Improvement and Proactive Practices

More and more companies are integrating impairment tests into their workplaces to proactively assess and manage safety risks due to fatigue, illness, emotional distress, substance abuse, and more.

Are you already using drug testing?

Impairment testing is the proactive practice that remedies for the reactive nature of drug tests.

Proactive practices such as impairment tests help ensure that a safety system is in a consistent state of improvement.

In a Positive Safety Culture, Communication Occurs Openly Between Departments, Members of the Workforce, and Management.

Communication is not just one-way and is always open and encouraged.

Yes, more communication. But it’s so important.

We’ve already provided two examples of miscommunication in this article:

- In #1 when a manager’s meaning was not appropriately conveyed resulting in assumptions

- In #2 when communication from management reflected double standards

Now, here’s another way to prevent them:

A great way to prevent miscommunication, whether it’s due to a misunderstanding of tone/language/vocabulary or a perceived double standard is to make sure that communication is open and encouraged.

Take, for example, a workforce with two managers.

One says to wear your helmet all the time.

The other walks around the site with his bare, bald head blinding everyone.

The workforce is left questioning how serious and necessary these safety practices really are.

What do you do?

You meet with the bald manager face-to-face and you make certain that you’re on the same page about your safety practices. Then, you both share the responsibility for enforcing these practices.

When a workforce’s supervisors supervise differently, the workforce does not have clear understanding about what exactly is expected of them:

Having this sort of meaningful, open communication may require a better medium of communication:

Many of the miscommunication issues related to over-reliance on memos, bulletin boards, and e-mails in place of face-to-face contact. People felt they didn’t have time to have conversations, but the results of miscommunication sometimes ended up costing a lot more.

An example that caused a lot of animosity occurred when a minimum manning policy was implemented. Grievances were filed because no one knew about it. Yet, it had been posted for over a year on a bulletin board because no one had read it . . . We should never assume that letters, memos or reports have communicated important information.

One of the Challenger accident investigators coined the phrase, “Information is not communication.”2

A Positive Safety Culture Uses Open Communication to Operate Optimally in a Singular Direction that is Clear to all throughout the Company.

It does not require the workforce to conform to the differing expectations of each supervisor overseeing them on a particular shift.

In a Positive Safety Culture - Management/Leadership Play an Active Role to Demonstrate that Safety of the Workforce is The Top Priority

Demonstrate.

Not just say.

When management says they prioritize worker safety and then somehow communicate the opposite, the workforce begins to mistrust management and their intentions.

How do you demonstrate that you prioritize safety?

Go to the worksite.

Gain first-hand understanding of their work environment and what happens on the front line.

Talk to your workers individually.

Take interest in their tasks and safety concerns.

Take their concerns seriously and act upon them.

Realize that you can’t understand the hazards of the job more than the workers facing these hazards daily.

You need to be present: “Employees [perceive] the lack of visible presence as lack of interest."2

And you need to be responsive: "Managers saw that responding to safety concerns and suggestions in a timely manner was at the heart of building trust and credibility."2

In a Positive Safety Culture, Incidents, Safety Issues, or Stopping Work for Safety Concerns are Not Met with Negativity

Negativity and reprimands are the most obvious indicators of a negative safety culture.

Responding to a safety issue with punitive measures sends a pretty ridiculous message: “Don’t hurt yourself or you’ll get in trouble.”

When workers are afraid of getting in trouble, your safety culture can’t take advantage of these mistakes to improve.

Here’s an example from Carrillo:

A worker received an electric shock but survived.

Then, “no one came forward to admit they had failed to tag the electrical outlet as faulty because they knew it would mean days off without pay at best, and dismissal at worst."2

Had management eased workers’ fears of being reprimanded or punished for incidents, and created a positive environment in which workers could come forward without fear, they could have understood the circumstances that led to the problem and learned how to avoid it in the future.

In contrast, punitive and negative safety cultures contribute to the accident cycle:

Workers don’t need to be punished for getting hurt.

Getting hurt is punishment enough.

What workers need is for management to create an environment where everyone is encouraged to be accountable and responsible.

Here’s how you can start to build such an environment:

Lead by example. Own up to your mistakes in front of your workers.

Build trust with your workers, so that they are not afraid to confide in you.

Communicate openly about your shared responsibility to identify and manage risks.

Conclusion

There certainly may be additional characteristics of a positive safety culture, and those outlined here could be given much more in-depth exploration. One important aspect of safety culture is that it is directly correlated with the bottom line.

At the heart of the characteristics discussed here, however, lay three key factors: communication, responsibility, and proactiveness.

Without mastering these three, you can’t have a positive safety culture.

Safety experts, academia, and modern workplaces are exploring the role of technology in strengthening these 3 factors, and thus building a more positive safety culture. At the forefront of this technology is impairment testing.

Impairment tests create a way for workers and supervisors to communicate daily and as necessary and technology can facilitate a strong safety culture. It helps them establish a relationship built on trust and care. It also spreads the responsibility for safety to every single person in the workforce because the test helps establish accountability. Finally, it is the picture of proactive. By identifying potential risks as workers file into the workplace, it allows risks to be managed before accidents occur.

Want to learn more? Get the Case Studies here!

Sources:

Bridges, K. (2013). Sharing responsibility for safety. The Safety & Health Practitioner 31(6): 17.

Carrillo, R.A. (2004). Breaking the cycle of mistrust to build a positive safety culture. Occupational Hazards 66(7): 45+. Retrieved from http://ehstoday.com/safety/best-practices/ehs_imp_37126

Teague, C., Leith, D., & Green, L. (2013). Symbolic interactionism in safety communication in the workplace. In N.K. Denzin & T. Faust (Eds.), Studies in symbolic interaction: 40th anniversary of studies in symbolic interaction (175–199). Bingley, UK: Emerald.

Weekes, J. (2014, December). 12 ways to promote a positive safety culture in your workplace. Health & Safety Handbook. Retrieved from http://www.healthandsafetyhandbook.com.au/

12-ways-to-promote-a-positive-safety-culture-in-your-workplace/