What is Workplace Fatigue?

Workplace fatigue is one of the most common, costly, and dangerous safety risks affecting safety-sensitive industries. It is often described in terms related to sleepiness, tiredness, or exhaustion and is discussed in contexts such as workplace safety, enhancing work productivity, or reducing fatigue-related workplace risks.

However, it is important to look beyond this context to achieve a fuller understanding of what fatigue is, what causes it, its implications, and how you can manage it most effectively.

First of all, fatigue is much more than a feeling of sleepiness. It can result from a variety of factors unrelated to sleep, and cause a variety of symptoms far more subtle and more dangerous than sleepiness. Secondly, the positive impacts of effectively managing workplace fatigue are much more comprehensive and wide-reaching than discussions limited to "improving workplace safety" or "enhancing worker productivity" may imply.

In order to fully appreciate fatigue's impact on workplaces, it's helpful to visualize its effects in three main states:

- Mental state: Reduced cognitive functioning and mental capacity

- Physical state: Reduced bodily functioning and physical exhaustion

- Subjective state: Feelings of tiredness, sleepiness, drowsiness

This categorization by the CSA group can help understand the different ways in which fatigue can present itself and thereby help determine the most effective countermeasures. Although they are categorized separately, it is important to recognize that these 3 states are interconnected. If an employee is showing signs of mental fatigue such as undertaking risky behavior, he/she is also likely to be suffering from subjective feelings of tiredness and physical exhaustion. If an employee is currently only experiencing fatigue in one state, they may either be in the earlier stages of fatigue or they may be suffering from a specific issue that is so far only apparent in one state.

For example, if a worker is experiencing sleepiness or drowsiness but they are not showing signs of mental and physical fatigue, a sleep-inducing allergy pill and/or boredom due to repetitive tasks are potential culprits. If a worker is physically exhausted but not mentally compromised or feeling drowsy, they've probably over-exerted themselves and need a water break or a nutritious snack. The mental state of fatigue is the most difficult to identify because the worker usually loses self-awareness when they are experiencing this state of fatigue and cannot self-report. For this reason, it is important to pay attention to physical and subjective states of fatigue as they may culminate in this much more dangerous state of mental fatigue when left unaddressed. The subtle and deadly nature of mental fatigue is also the reason every workplace needs a robust and proactive fatigue risk management program.

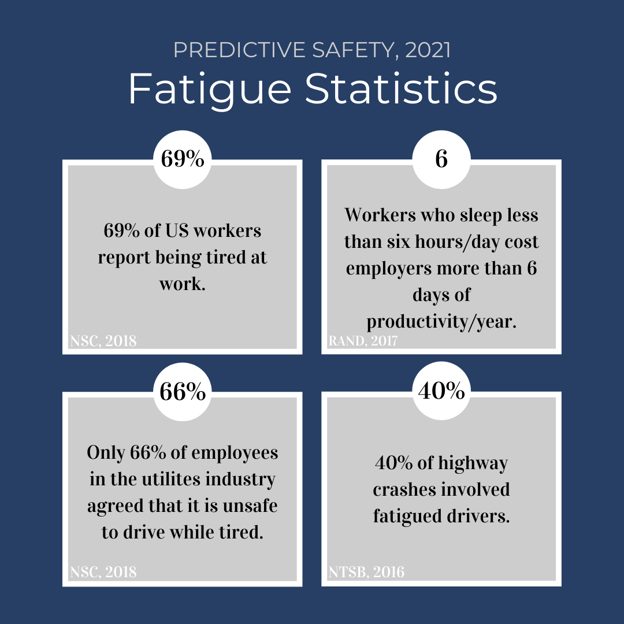

Now that you're thinking about workplace fatigue in broader terms than just "tiredness", it's essential to understand just how big of an issue this is. Check out these recent workplace fatigue statistics:

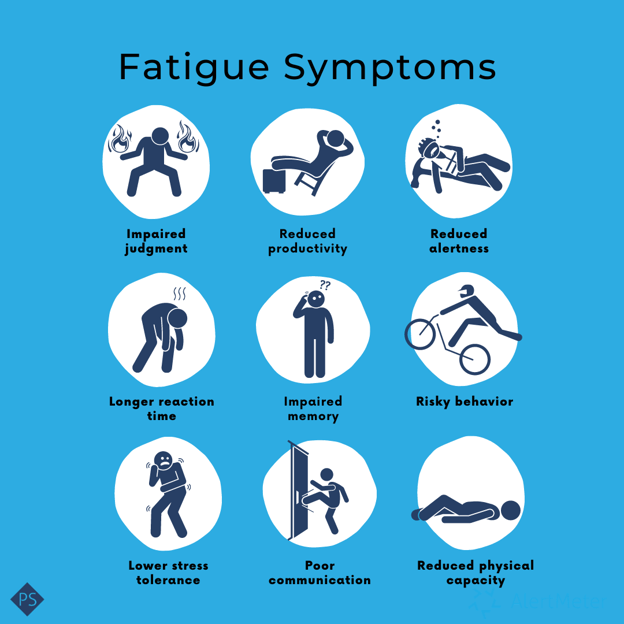

Symptoms of Workplace Fatigue

The following are common symptoms of fatigue, according to CCOHS.

- reduced decision-making ability or cognitive processing

- reduced ability to do complex planning

- reduced communication skills

- reduced productivity or performance

- reduced alertness, attention and vigilance

- reduced ability to handle stress on the job

- reduced reaction time - both in speed or thought, as well as the ability to react

- loss of memory or the ability to recall details

- failure to respond to changes in surroundings or information provided

- unable to stay awake (e.g., falling asleep while operating machinery or driving a vehicle)

- increased tendency for risk-taking

- reduced physical capacity

- reduced performance, such as a reduced ability to do task or job

- impaired memory

- increased errors in judgment

Although some of these symptoms can be categorized into the subjective or physical states of fatigue, the majority fall under the mental state of fatigue. Symptoms such as impaired memory, errors in judgment, or reduced decision-making abilities, for example, can be extremely dangerous in a safety-sensitive or healthcare work environment. Although these symptoms may be hard to recognize even when you know what to look for, it's critical that they are noticed and addressed promptly and appropriately. An effective workplace fatigue risk management program will empower managers to do just that. The following section highlights key characteristics of a workplace fatigue management program.

Workplace Fatigue Management Plan

The most important thing to remember about managing fatigue is that it requires an objective and proactive effort every day. Due to its subtlety, managers must implement a way to "catch" fatigue before it catches workers.

Once fatigue "catches" workers, it's more difficult to identify because of the ensuing detriment to self-awareness and decision-making. In fact, one study showed that fatigue due to 24 hours of sleep deprivation has a cognitive performance decrement equal to that of a 0.05% BAC. For those working consecutive night-shifts, the cognitive performance decrement was shown to be even more significant. (Dawson, 1997) Knowing that their judgment, vigilance, reaction time, and other executive functions would be dangerously impaired, most people wouldn't let their drunk friends make the decision to drive themselves home. However, night-shift workers regularly drive home at a time when their cognitive impairment is reaching levels far beyond what the 0.05% BAC limit would permit.

This is why an effective fatigue management plan requires an objective form of measurement--similar to the use of a breathalyzer for alcohol impairment--that can be relied upon in the absence of sound worker judgment and self-awareness.

Consider this story from one of our customers who use the AlertMeter® app to identify cognitive impairment in their employees:

An employee who operates a 90-ton crane scored abnormally on two consecutive tests. When approached by the supervisor, the employee admitted to having been awake all night at the hospital due to a medical emergency with his child, and he decided to come to work to “get his mind off it.” Instead, the employee was sent home with pay.

Due to his lack of self-awareness which was further compounded by the emotional toll of having a sick child, this worker could not be trusted to make a self-assessment and follow sound judgement in making decisions concerning his own safety and the safety of his team. The manager's ability to proactively and objectively identify this worker's impairment may have prevented a terrible accident that day.

To sum up, an effective fatigue risk management program will be proactive and objective. It must be able to predict fatigue before it hits (such as our predictive fatigue risk management system PRISM) and/or be able to identify it in real-time using an objective measure (such as our 60-second cognitive impairment app, the AlertMeter®).

If you haven't implemented a fatigue risk management program yet, there are still some key steps you can take to curb fatigue risk in your workplace. For maximum impact, share these tips with your workers and find ways to practice this fatigue-awareness in your daily workplace routine.

10 Steps in a Fatigue Management Plan

There is No Substitute for Sleep

Most of us need an average of 7 to 9 hours of sleep each night to fully recuperate from a regular day’s work, both physically and mentally. Sleep is the only way we can fully and properly recover from fatigue. However, we can stay alert during a period of fatigue by strategically using countermeasures such as a well-timed cup of coffee, stabilized blood sugar through snacking or protein or complex carbohydrates, and sufficient hydration.

Stimulants Only Help so Much

Although caffeine and energy drinks can remedy fatigue symptoms in the short-term, they should be well-timed and used

sparingly. If the body is already fatigued, chemically-induced stimulation will be short-lived and lead to a more pronounced onset of fatigue symptoms. Other countermeasures such as high-protein snacks and mild physical activity may be a better choice for staying alert as the end of shift gets closer.

Workplace Fatigue is Serious Business

Laboratory studies have clearly proven that fatigue impairment can be equal to or greater than alcohol impairment. However, few workplaces take it as seriously. Acknowledging fatigue as a real safety risk and adopting successful solutions for managing it will encourage employees to be more open and honest about its effects on them.

Fatigued people are often the last to recognize their own fatigue symptoms. Watch out for these telltale signs of worker fatigue:

- Loss of concentration

- Poor decision making

- Cutting corners

- Mood swings

- Short-term memory loss

- Slowed reaction times

- Reduced risk perception

Shiftwork is a Major Cause of Workplace Fatigue

The human circadian cycle naturally wants to keep the body alert during the day and asleep at night, and this propensity will fight even the most seasoned night shift worker.

Other causes of fatigue in shiftwork include:

- Rotating between day and night shifts

- Not giving the body enough time to rest between shifts

- Poor living/sleeping conditions preventing restorative sleep

- Insufficient time allowing the body to adapt to changing shift schedules

Environmental Factors can Cause Workplace Fatigue

Noise, the wrong lighting, high heat, humidity, machine vibrations, and other environmental factors can all

contribute to fatigue. With a little research, you may find lighting that is more comfortable on your eyes than what you currently use. And noise mitigation can have a remarkable impact on employee fatigue levels.

In work environments where heat or humidity are high, keeping employees hydrated and having frequent breaks can help control the onset of fatigue symptoms.

Alertness Varies by Time of Day

Become familiar with the two circadian lows, generally occurring in the early morning and early afternoon hours.

People are naturally less alert at these times, so their task scheduling and performance expectations should be adjusted accordingly.

Using an impairment monitor designed to consider the work and sleep history for individual employees will help them become more aware of and plan for their own energy slumps during their shifts. Check out PRISM, our predictive fatigue risk management app, here.

The Ability to Easily Fall Asleep Varies by Time of Day

Generally, most people fall asleep naturally between 10:00 p.m. and 11:00 p.m. There is a period of wakefulness before this, from about 6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m., when it is difficult for most people to fall asleep. Where practical, avoid or minimize consecutive shifts where employees will need to sleep at the times when falling asleep is most difficult. It is also difficult to fall asleep when the internal drive to be awake reaches its daily peak. For most people, this occurs in the late morning.

Early morning alertness peaks may be slightly later after a series of night shifts.

The Amount of Time Needed to Recover from Fatigue Depends On Time of Day

While it is reasonable to expect employees to get an adequate amount of sleep during a normal overnight break of 12 hours, it is not reasonable to expect that they will get adequate sleep in a 12-hour break that begins in the morning.

If possible, allow employees longer periods off if they must sleep during the day.

Sleep Loss is Cumulative

As a pattern of shift work continues, the effects of sleep loss and poor quality sleep accumulate, leading to increasing drowsiness and performance impairment as the workweek progresses. Two full nights of uninterrupted sleep within the normal self-selected sleep time of 10:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m. are required for adequate recovery after periods of overnight work.

Provide breaks with at least two full nights off as part of the normal shift schedule.

Education Plays a Big Role in Minimizing Workplace Fatigue and Promoting Better Sleep

Good education about fatigue leads to workers who can manage their hygiene more successfully. Shift workers can be given strategies to improve their quality of life and sleep, such as improving their sleep facilities, engaging family members to understand their supportive role, and avoiding caffeine or alcohol within the hours before sleep.

Good topics to cover in educational sessions include:

- Adjusting the sleeping area to promote good sleep

- Good nutrition while working shifts

- Use and avoidance of stimulants

- Recognizing the signs of fatigue

- Fitness and exercise Effective napping

- Equal facilities for shift workers

Conclusion

The modern workplace is gradually dismantling the "sleep when you're dead" attitude towards work and sleep. However, there are still many workers and managers who see fatigue as a sign of weakness, or prioritize work demands over basic physical and mental health. What's more basic to human health than a good night's sleep?

As scientific research and modern technology have made apparent, fatigue is more widespread, more disastrous, and more preventable than previously understood.

By recognizing that fatigue is rampant in safety-sensitive workplaces, understanding how disastrous it truly is, and how preventable it has now become, workplaces can take 3 big steps toward significant reductions in accident rates, significant reductions in accident costs, and significant improvements in worker productivity and morale. If you've already taken these 3 steps, you may be ready to schedule a demo with us to discuss our two highly successful workplace fatigue management apps--PRISM and AlertMeter®.

More Resources:

6 Reasons Why Your Company Needs to Manage Work Fatigue and Impairment (Part 1)

6 Reasons Why Your Company Needs to Manage Work Fatigue and Impairment (Part 2)

3 Things Workers Should Know About Shift Worker Fatigue, From a Doctor

Managing Safety through Worker Fatigue Data

Circadian Rhythm and Shift Work - When the Time Changes

The Factors of Fatigue and the Fatigue Assessment Scale

3 Ways Sleep Sleep Apnea at Work is Costing Your Business (And How To Fix It)

4 Steps to Fatigue Risk Management - a Fatigue Risk Management Template

6 Fatigue Countermeasures

Fatigue in the Workplace: Myths vs. Realities

Work Fatigue Symptoms

Predictive Safety Featured On the WorkSAFE Podcast: Tech Designed to Stop Fatigue Impairment Risk in Its Tracks

The Science of Fatigue at Work

Real-Time Fatigue Monitoring & Management Software

References:

Al Ma'mari, Qasim, Loai Abu Sharour, and Omar Al Omari. "Fatigue, burnout, work environment, workload and

perceived patient safety culture among critical care nurses." British journal of nursing 29.1 (2020): 28-34.

Dawson, D., Madeline Sprajcer, and M. Thomas. "How much sleep do you need? A comprehensive review of fatigue

related impairment and the capacity to work or drive safely." Accident Analysis & Prevention 151 (2021): 105955.

Dawson, D., Reid, K. Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature 388, 235 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1038/40775

Harnett, M., Kumagai, J. (October, 2019) Workplace Fatigue – Current Landscape and Future Considerations. CSA Group.

Epstein, M., Söderström, M., Jirwe, M., Tucker, P., & Dahlgren, A. (2020). Sleep and fatigue in newly graduated nurses

—Experiences and strategies for handling shiftwork. Journal of clinical nursing, 29(1-2), 184-194.

Marcus, J. H. & Rosekind, M. R. (2017). Fatigue in transportation: NTSB investigations and safety recommendations.

Injury Prevention, 23 (4), 232-238.

Yogisutanti, G., Aditya, H., & Sihombing, R. (2020, February). Relationship Between Work Stress, Age, Length of

Working, and Subjective Fatigue Among Workers in Production Department of Textiles Factory. In 4th International Symposium on Health Research (ISHR 2019) (pp. 70-73). Atlantis Press.